I’ve been in Madrid for just over a week now. At noon on a Sunday, I said goodbye to country life and handed over the duties to a new workaway. Then off on the bus and into Europe’s sixth-largest city, which was of course an overwhelming change of scenery. To be honest, I missed the tranquillity of the countryside after just one day, feeling a little crushed by the size of Madrid and the multitude of options the city offers. To free myself from this situation, I first had to learn how to find my way around this asphalt jungle.

Fortunately, Madrid has one of the best metro networks in the world, complemented by commuter trains, trams (or “Metro Ligero” in Madrileño) and an extensive bus network. So public transport here is rather accomplished. Metros run until two in the morning every day, the timetables are very tight and so far I’ve hardly had to squeeze into an overcrowded carriage like a human sardine. The icing on the cake is that, due to rising inflation and the cost of living, the prices for ten-ride and monthly tickets are currently reduced to ease the economic pressure on city dwellers; in truth, the reason for the cheap fares has nothing to do with icing on cakes, but it suits me.

However, it is not at all convenient to want to use the only form of individual mobility that I find 100% worthy of support: the bicycle. One of my favourite things to do in any city I visit is to get a bike and try to explore the city. However, I don’t feel like doing that in Madrid. I see very few people on bikes, and I’m not surprised. It’s not that there are no bike lanes; there are. But they are not connected at all, especially if you want to get out of the city centre. You can see this lack of connection very clearly if you look for the way from Alcorcón, where I live in a family friend’s flat, to the bicycle frame building school where I will be taking a course at the end of March. Getting there by bike involves crossing two motorways on footbridges, conquering an eight-lane road junction and mastering several huge roundabouts that would make me feel tiny on a bike.

Nevertheless, I would like to ride this route once to see what it is like. The problem is that I, a fit person who has been cycling in cities for years, don’t feel comfortable on a bike here. This makes it clear why cycling is a sporting hobby here and not a means of transport. It may be quite different in other corners of the city, but in the South West, cycling is not an option. And it’s not that there are no counter-examples in Spain. Barcelona, the second largest city in the country, has been radically reforming parts of the city to further sustainable mobility. I have also heard a lot of good things about Girona as a very “bike friendly” city. I am sure there are a few more examples.

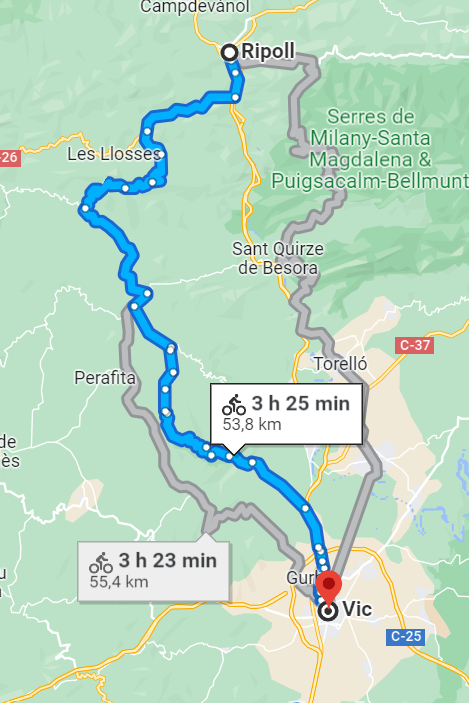

Since I’m already lost in this cycling thing, I’d like to dive a little deeper and share an anecdote from a cycling trip to Catalonia I undertook with Anita two years ago. Back then I felt similar to when I realised that Madrid’s neighbourhoods are not connected at all with roads suitable for cycling, let alone cycle paths. On our journey, we had reached the town of Ripoll in the foothills of the Pyrenees, and the destination was Vic, a larger town south of Ripoll. Between the two towns there is a valley through which a motorway has been built. Thus, by car, it takes 30-35 minutes to get from one town to the other, and you only have to drive about 35 kilometres without any significant incline. By bike (except MTB) you have to leave the valley and cover at least 55 kilometres and 600+ metres of altitude. We tried to ride the MTB route with our touring bikes. After many hours without much progress, we found a road cyclist who took us to the nearest train station via the motorway (BECAUSE THERE IS NO OTHER ROAD THAT GOES THROUGH THE VALLEY). What amazes me is the predominance of the automobile in this example. The old road was cut up to build the motorway and it is no longer possible to enjoy the valley by bike or any other slow means of transport that cannot go off road.

To return to the present and to Madrid, it seems to me that there is a connection between the highly developed metro system and the asphalt jungle. Because it is so easy and relatively convenient to get around the city by metro, the car has gained the upper hand – or maintained its dominance – which means noise (cities don’t make much noise, cars make noise), air pollution and an absurd amount of space needed for wide roads and car parks. To sum up, Madrid faces a tour de force in the next ten years to promote more sustainable mobility, which I think is inevitable since the maximum temperature in summer already reaches 40 degrees Celsius.